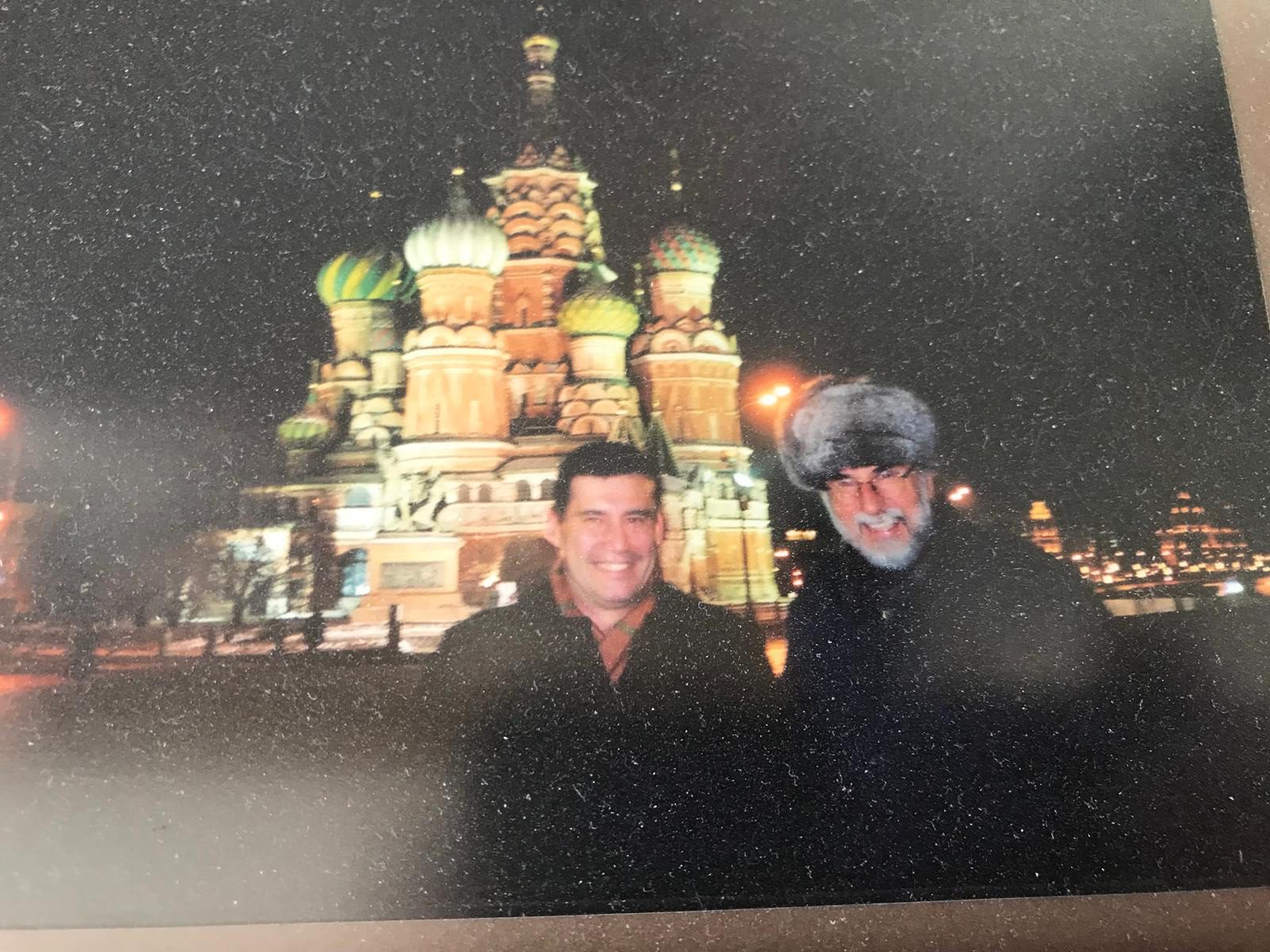

The AEJ’s Tony Robinson, former FT Russia and Eastern Europe correspondent, has just returned from the funeral for Derk Sauer, founder, media entrepreneur, and independent chronicler of news in Russia for more than 30 years.

Robinson has this tribute to a man who made an “outsized contribution to modern journalism in Russia. We worked together for two years in Moscow, launching Vedomosti.” The Moscow Times, founded by Sauer in 1992, is still publishing independent news from Russia.

Funeral of Derk Sauer, media hero

By Anthony Robinson

Amsterdam’s vast gothic Westerkerk erupted with applause as a packed congregation of family, friends and business partners greeted the coffin holding Derk Sauer, entrepreneurial founder of the Moscow Times and the Russian language business newspaper Vedomosti.

Derk, who died on July 31 of complications after his sailboat hit an underwater rock off the Greek islands last month and whose obit by Simon Kuper was published in the FT on August 3, introduced western-style independent journalism to post-Soviet Russia which enriched and informed a traumatised society and played a crucial role in its oil-fuelled, oligarch-led transition to a market economy.

Backed by both the FT and the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) the ground-breaking new venture was eventually named Vedomosti, after much discussion, in honour of Russia’s first newspaper, Peterburgski Vedomosti, essentially the official gazette of Czar Peter’s new capital, St Petersburg.

Vedomosti was conceived as Russia’s 21st century “window on the world “- a business newspaper which, with access to news, comment and advice from both its foreign media partners, widened the international horizons of nascent Russian entrepreneurs and provided insight into opaque but populous, resource-rich Russia for mainly US and European investors.

Two or three times Derk attempted without success to launch a Russian language business newspaper to complement his Independent Media’s successful English language Moscow Times and Russian language versions of glossy magazines from Cosmopolitan to Men’s Health, working closely with his wife Ellen Verbeek.

Unbeknownst to him, I had come to a similar conclusion after many years as FT Moscow correspondent and East Europe editor. While on sabbatical in Italy I drew up a detailed editorial plan for such a newspaper, and presented it to David Bell, chief executive of the FT, at a meeting at the HQ of Pearson, the FT’s then owner. He accepted my proposal – but added “now find me a publisher.” But it was he who contacted Derk and sent me to Amsterdam to discuss my ideas with Derk and his canny Dutch investors.

Derk enthusiastically accepted my proposal, with its prospect of close co-operation with the FT and Pearson, which at the time was riding the dot-com boom and branching out into foreign language newspapers and magazines, including FT Deutschland. But before setting aside $5m for the project,Marjorie Scardino, head of Pearson, contacted Karen House, her counterpart in the WSJ. It helped greatly that both hailed from Texas.

They were head to head rivals in the global business newspaper market. Both were interested in the potential of the Russian market. But given the unquantifiable risks of going alone they decided to jointly work with the proven Dutch publisher in Russia. Thus was born the unique “marriage a trois” between Independent Media, FT and WSJ.

Just how risky and unpredictable “the riddle, wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma”, in Churchill’s immortal words, Russia was and is, was made dramatically clear on arrival at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport with my wife and three small boys on August 18, 1998. On that day Russia’s financial bubble burst. The rouble nosedived, banks closed – but only after those who received tip-offs scurried around town stuffing dollar notes into vast sports bags.

It took many a fraught telephone conversation with London to persuade Pearson not to cancel the project before birth. Rouble devaluation, I argued, was a boon for the project, not a disaster. Firstly, deep devaluation meant that the costs of the project, from office rent to salaries would plummet. Not least, bravely coming to Russia at one of its darkest hours, and employing hundreds of young Russians, would be remembered by the powers that be, and even ensure protection from future problems.

The latter point was quickly disproved by Vladimir Putin. He came to power four months after Vedomosti’s launch in September 1999 and began a relentless attack on Russia’s independent media with the exile of Vladimir Gusinsky and the expropriation of his independent TV company, NTV.

To keep the show on the road, Shelly, my wife, and our three boys had to return to London, while I stayed on in Moscow to thrash out the details of the new business paper with Leonid Bershidsky, the brilliant but acerbic 27 year old nominated editor, and hang on for two years as consulting editor.

So began the hardest and loneliest years of my life – but as witness to the exhilarating and hugely successful launch of the low-cost, digital newspaper by its young ambitious staff who made Vedomosti an admired, reliable, almost cult newspaper.

Derk’s openness to new ideas is reflected in his personal transformation, from lefty Maoist hippy attracted to the disintegrating Soviet Empire into the creative champion of independent media, civil society and capitalist values. It was a transformation that could only have happened during the painful but liberating chaos of the Yeltsin decade.

But well before 2017, when Putin killed off Vedomosti and other independent publications with foreign shareholders through a draconian new press law, Derk and his Dutch partners saw the writing on the wall and sold their stake in Independent Media (IM) to the Finnish media group Sanoma in 2005 for Euro143m.

Derk agreed to stay on in Moscow as CEO and then chairman of Sanoma’s supervisory board until 2013 when he became president of the Russian business news agency (RBC). Two years later Vladimir Zhirinovsky, firebrand leader of the extreme nationalist and ironically mis-named Liberal Democratic (LDPR) party, with close links to the security services, called on the Duma to remove Derk from the RBC and called for his expulsion from the country.

Vedomosti’s attraction to Sanoma, and the loyalty of its readers and advertisers, relied on its editorial independence and support from foreign shareholders. It profited from Russia’s economic recovery, underpinned by the Yeltsin era reforms. Recovery turned to boom in the new millennium as economic growth was supercharged by rising oil and commodity prices which Putin had the great good fortune to inherit.

Vedomosti ‘s editorial team was made up exclusively of talented young men and women who had no experience of working for Soviet era publications but were eager to work long and hard under the new conditions. For many the experience and prestige gained by working in Vedomosti and other IM publications opened the door to subsequent good jobs throughout business – and even in the Kremlin.

Alexander Gubsky, former deputy editor of Vedomosti and now publisher in exile of the Moscow Times, recalled that with the launch of the Moscow Times in 1992 “Derk brought real journalistic standards to Russia; separating news from opinion: requiring two independent sources for news and so on. Derk also opened a training school for Russian journalists right inside the paper.”

At Vedomosti’s launch in September 1999, editor Bershidsky set the tone in his first editorial. “Vedomosti will remain independent of political influence, not only because our foreign founders and shareholders are publishers who have no other political or financial interests in Russia – apart from the success of Vedomosti.”

“We also have a rather specific attitude towards such traditionally Russian phenomena as ‘black PR’, inspired leaks and the compromising material called ‘kompromat.’ Those who try to use our newspaper as a channel for such devices will find that the attempt could turn against them. After receiving such an offer we would disclose who would hope to benefit from the publication of such information, and in what way.”

Despite, or possibly because of, this uncompromising policy Vedomosti was enthusiastically welcomed and supported by ambitious, rival oligarchs. They had become enormously rich by expropriating pathetically under-performing Soviet assets and transforming them into functioning, wealth-creating companies and yearned for recognition and respect.

As proven successful businessmen, Derk and partners invested in the administrative, financial and advertising revenue earning functions to underpin Vedomosti’s independence. While negotiating editorial agreements with the FT and the WSJ, Derk also secured six months of guaranteed advertising revenue in advance from a supportive group of oligarchs who ran Russia’s new economy.

Both foreign media partners supported Vedomosti in various ways. But perhaps the most valuable, and not part in any way of the original deal, stemmed from the realisation by Derk and Ellen Verbeek, his wife and business partner, that the FT’s hugely successful glossy monthly supplement “How to spend it” had an enormous potential market among Russia’s nouveaux riche and glamour starved aspirants.

Lucia Van der Post its creator feared “contamination” of the London original by a Russian version. But Derk insisted and “Kak potratit” – full of brilliant original Russian content – including stunning Russian models, attracted an enthusiastic audience and oodles of advertising revenue.

Of all the crimes and misdemeanours of the Putin regime, the deliberate destruction of Russia’s independent media ranks highly among the wider damage and degradation of Russian lives and hope brought about by the systematic abolition of the political, social and cultural institutions which emerged in the first post-Soviet decade. Instead, Putin and his cronies have used Russia’s windfall wealth to rebuild the police state and the military,

This led to the invasion of Ukraine and exodus of hundreds of thousands of Russia’s best educated and skilled young people. Among the exodus were many journalists. Derk and his partners reacted by offering refuge and support in Amsterdam not only for journalists from the Independent Media stable but also independent TV stations such as Dozhd (Rain), the Meduza news agency and others – many of them condemned as “agents of a foreign power” by Putin.

Helping to keep the flickering flame of independent Russian media alive is a key part of the legacy which Derk’s untimely death leaves behind him. The baton has been handed to Derk’s second son Piotr who inherited his passion for journalism, grew up in Russia with his two brothers and speaks Russian with a fluency which Derk, for all his trying, never quite managed.

Derk Sauer Obituary – FT 3 August 2025

Derk Sauer – The Moscow Times 1 August 2025

Derk Sauer “champion of free press in Russia” – New York Times 1 August 2025

Obituary for Derk Sauer – The Guardian 8 August 2025