From William Horsley, AEJ UK chairman and an executive committee member of the Commonwealth Journalists Association

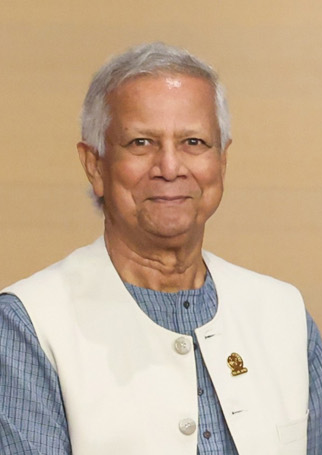

Last week London provided a crucial international stage for the Nobel Peace Prize laureate and Chief Advisor to the Bangladesh government, Professor Muhammad Yunus, to present a positive account of his efforts to restore democracy there in the ten months since the harshly authoritarian government of Sheikh Hasina was overthrown in a student-led uprising last summer. Prime Minister Hasina’s flight from Dhaka into India on 5 August was preceded by extreme acts of violence in bloody street clashes between police and anti-government protestors. After the government fell, police forces across the country were the target of widespread retaliatory violence, and with many police officers too afraid to perform their duties law and order broke down for several weeks.

Political conditions in Bangladesh – the world’s eighth most populous country — remained volatile as Prof. Yunus arrived in London on June 11 for a 4-day visit. Heightened tensions between Dhaka and Delhi have contributed to the muted international attention paid to reports of the arbitrary suppression of political and legal rights under the interim administration led by Muhammad Yunus. On June 11, when Dr Yunus spoke at a packed meeting at Chatham House, he set out his plans for a 3-part political settlement, including sweeping reforms, the trials of those accused of wanton violence and killings during the uprising, and elections next year.

Questioned about persistent reports about a clampdown on the media at home, Dr Yunus flatly dismissed the suggestion. “People have never had so much freedom in their life”, he declared, adding “The media can say whatever they like”. That assertion is fiercely contested, however. While Professor Yunus deserves understanding and support for his efforts to fulfil the arduous task he was asked to take on, his brusque denial has not gone unchallenged. Critics describe a very different reality in Bangladesh from the one he described to his London audience.

A prominent journalist couple, Farzana Rupa and Shakil Ahmed, are among those who have been imprisoned since they were arrested last year. So are two members of the Commonwealth Journalists Association who were deposed as senior media editors: they are Mozammel Babu and Shyamal Dutta, a CJA vice-president, who was also ousted as secretary-general of the Bangladesh National Press Club. All four face charges of murder and other anti-state crimes based on so-called First Information Reports (FIRs) which the detainees’ lawyers and family members maintain contain no material evidence linking them with the crimes of which they are accused. Yet reports say that no serious investigations have taken place into the alleged offences, the detainees’ applications for bail have been repeatedly and cursorily denied, and complaints against harsh prison conditions and restricted access to lawyers have gone unanswered.

A widespread retaliatory purge of media outlets sympathetic to the ousted Hasina regime is clearly taking place, which has seen at least six journalists killed, dozens of media offices ransacked by mobs, hundreds of journalists summarily dismissed from their jobs and deprived of their press accreditations, and many media houses forced to replace their owners. In January, lawyers for Rupa and Ahmed initiated complaints procedures to the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention and the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression, Some argue that recent developments amount to a pattern of disregard for due legal process and basic human rights in Bangladesh that mirrors the hated practices of the former regime.

During his appearance at Chatham House Muhammad Yunus was challenged about the government’s insistence that the Awami League formerly led by Sheikh Hasina would be barred from competing in elections next spring. Was it not authoritarian to exclude from the political debate anyone who did not agree with the proposed “charter” for national unity? He replied that the Awami League should remain suspended until the trials of those who had committed “terrible crimes” — including the killings and forced disappearances of protestors and government opponents — had taken place.

That answer from Bangladesh’s interim leader is cold comfort for those who languish in prison complaining that their basic rights are being arbitrarily denied, and whose families fear that their fate is being ignored by the outside world. In that context, the failure of the British Prime Minister or the Foreign Secretary to meet Professor Yunus during his recent stay was a missed opportunity to express the UK’s unwavering commitment to the rule of law and universal human rights standards, while offering helpful but critical support to a large member state of the Commonwealth.

The awkward silence of the Commonwealth itself, under its newly-installed Secretary General Shirley Botchwey, will be seen by some as a failure to re-assert the Commonwealth’s relevance — especially so soon after the adoption of a landmark agreement in the field of civil, political and media rights at the Heads of Government meeting in Samoa last October. In the Commonwealth Principles on Freedom of Expression and the Role of the Media all the Commonwealth heads of government accepted their responsibility to ensure a safe and enabling environment for media workers, so that they can work without fear of violence, abuse, intimidation, discrimination or interference.

Professor Yunus came to London to receive in person the ‘King Charles Harmony Award’ for his unquestioned contribution to socially responsible projects and poverty reduction. So it is ironic that the visit took place amid a pall of silence about alleged injustices while far-reaching constitutional and political reforms are being implemented under his authority in Bangladesh.