Italian journalist Fernando Mezzetti, one of the most prominent international reporters of his generation, is remembered in this personal tribute by his long-time friend Anthony Robinson, AEJ UK member and former foreign correspondent for the Financial Times in Rome and elsewhere.

Mezzetti died in Italy on 10 May aged 81 after a prolonged illness.

He worked for Il Giornale and la Stampa as a foreign correspondent in Beijing, Moscow and Tokyo and continued to write editorials for Il Giornale di Brescia and other regional Italian papers after his retirement.

He wrote a dozen books on foreign affairs and modern Italian history on subjects including the rise and fall of fascism, Vladimir Putin’s rise to power, and From Mao to Deng on the transformation of China.

On 6 June Anthony attended the memorial mass in Fernando’s memory in the ancient Basilica of San Simpliciano in Milan, near his home town of Tradate in northern Italy.

Fernando Mezzetti –In memoriam

By Anthony Robinson

Milano during the “autumno caldo” of 1969 was a turbulent city. Striking factory workers marched through the main streets and violent clashes took place every night between armed police and “revolutionary” students, inspired by the May 1968 events in Paris.

Shadowy “red brigades”, neo-fascists, and anarchists plotted. Some “fell out” of police station windows during interrogation by Fascist-era remnant police. A mass funeral service for victims of a deadly bomb inside the Banca dell’ Agricultura filled the spiky Gothic cathedral while hushed crowds waited outside in the freezing fog.

Many of the brave, hard pressed journalists covering the chaotic events and their politically toxic consequences were either based in the monolithic Palazzo della Stampa, built in Mussolini’s time, or rushed in and out to check with Ansa, the Italian news agency, or file their copy. Fernando in particular caught my eye.

As the newly arrived Reuters correspondent, charged with setting up a Reuters Economic Services bureau, I had an office in the Palazzo and picked up much of what I knew from my new Italian colleagues. Fernando, the same age as me, full of life and energy, always in a hurry, was the man I instinctively liked the best. Small, agile with a shock of jet black hair and a ruddy complexion which contrasted with a pale scald-burn from infancy on his forehead, was unmissable. What we found out later was that we found the same sort of thing hilarious – usually pomposity and hypocrisy, and variants thereof.

After moving from Reuters and Milano to the Financial Times FT based in Rome, I picked up an affection for the ancient Etruscans and their joyous way of life as portrayed in their elaborate tombs. When I told Fernando he was delighted. We were both born in 1942. While I was born in grim, heavily bombed Grimsby, Fernando entered the world in Marta, a sleepy ancient little town that flanks glorious Lake Bolsena whose deep, clear waters cover the decayed rim of a giant extinct volcano.

It suddenly clicked. Marta and Lake Bolsena lie at the heart of ancient Etruria. For me, Fernando inherited and personified all that I imagined a true Etruscan would be – certainly in his lust for life and appreciation of friendship, culture – and taste for good food and wine.

After Italy our paths diverged. I returned to the UK and was appointed East Europe editor. We lost contact. But we recognised each other immediately when we met again almost a decade later, unexpectedly, in Havana, Cuba. We had both been sent to cover the surreal summit meeting of the now long defunct Non-aligned Movement (NAM) and the head on clash between Moscow’s man Fidel Castro and Yugoslavia’s President Tito.

The fate of the movement was in the balance. Should it be “non-aligned” but leaning towards Moscow, active protagonist in the Cold War, or look to the nominally agnostic but discreetly Western-backed Belgrade for succour and inspiration?

The NAM summit attracted a Macedonian salad of what were then called “third world” nations, including rival factions of the Pol Pot regime, the President of Afghanistan, who was assassinated on his return home, and left-wing ideologues of all descriptions, including the French revolutionary intellectual Regis Debray, with whom we shared a taxi ride. Our scathing criticism of the real Soviet Union was dismissed with a lofty “intelligent, but wrong” verdict from the haughty, wealthy Debray.

We were on our way to the keynote event – rival speeches in a huge stadium by Fidel and Tito. Fidel, as usual, droned on and on, but at a certain point he praised the Cuban armed forces, 50,000 of whom were rented out to Moscow to help spread the revolution in Angola and Mozambique, but also the Horn of Africa. As Castro triumphantly name-dropped a series of battles in Abyssinia, Fernando could not stop laughing. The battles quoted by Castro he told me between giggles were in the same places as those “victories” proudly announced by Mussolini four decades earlier.

Fernando’s talents as an “enviato” or “fireman” sent to cover tricky foreign wars and events were recognised by the upstart new paper Il Giornale which appointed him as a full time foreign correspondent and sent him to Beijing in 1980 and then to Moscow in 1983. Il Giornale, founded by the acerbic and brilliant Italian journalist Indro Montanelli, was a beacon of independent reporting in a country where most of the media was owned and to varying degrees controlled by big financial or industrial groups or political parties.

Fernando, with his historical knowledge of the Fascist regime and day to day experience of how the Italian communist party operated and its influence on Italian cultural life, plus those two years in Beijing at the beginning of Deng Tzao Ping’s reforms, must have made him been a brilliant Moscow correspondent.

I can’t say for sure, because no sooner had Fernando arrived in Moscow in April 1983, to my great joy, than the supposedly “jazz loving, whisky drinking” long-time Politburo supervisor of the KGB, Yuri Andropov, who had succeeded Leonid Brezhnev, decided to expel me. I was accused of “activities incompatible with my status” while the government newspaper Izvestia denounced me for “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.”

An upside to my otherwise sad expulsion was the opportunity to get acquainted with Dada, Fernando’s elegant, discrete and wise wife and companion. With Dada’s help, Fernando organised a spectacular farewell party for me and my daughter Joelle, inside the seven days that the Soviets gave me to leave the country. Despite having just arrived in Moscow, Dada and Fernando not only managed to pull in journalist friends and colleagues but several diplomats, including the US Ambassador and his wife. They parked the Embassy Cadillac with its Stars and Stripes pennant, right in front of the militia box guarding the entrance to their flat.

The British Ambassador was also invited, but declined. He was otherwise occupied – entertaining the former UK Prime Minister Harold Wilson at the head of a delegation from the UK-Soviet Friendship Society!

Our paths parted again. After leaving Moscow, Fernando made lots of new friends in Tokyo, by this time as correspondent of Torino- based La Stampa, owned by the Agnelli family, owners of Fiat. But in 1999 he returned to Moscow briefly while I was busy helping to set up a Russian language business newspaper called Vedomosti. It was a 100 per cent foreign-owned, independent newspaper jointly owned by the FT, the Wall Street Journal and Independent media owned by a group of Dutch entrepreneurs and Dirk Sauer, the brilliant creator of the excellent English language free sheet Moscow Times and Russian editions of glossy magazines. Putin closed it down five years ago with a new press law.

We spent a couple of riotous days wandering around Moscow, visiting old haunts and comparing Boris Yeltsin’s troubled “free Russia” –with plenty of problems but a free press and no political prisoners – to the paranoid Soviet Union in its declining years. As 1999 ended Vladimir Putin was handed the reins of power – and the long slide back to autocracy, Imperialism – and war began.

I don’t know how he did it, given the exhausting business of covering foreign countries on a day to day basis, but Fernando also wrote a number of deeply researched books. They ranged “From Mao to Deng” on the transformation of China, to diplomatic relations between Stalin’s regime and Mussolini, and included a book on daily life in Japan and another on Gorbachev’s traumatic attempt at reform –all drawing on his personal knowledge and historical research. He also wrote a perceptive early biography of Vladimir Putin, which he asked me to translate into English, and add my own comments and relevant material.

Unfortunately, the updated translation was never completed, events were moving too fast, but I did also forage around the archives in Kew at his request, on another subject. Fernando strongly suspected, based on his research, that the British secret service, acting on specific instructions from Churchill, was responsible for killing Mussolini, leaving the corpse to be shot up shortly afterwards by the partisans. His mutilated body was then strung up by the ankles, alongside Clara Petacci, his mistress, at a petrol station outside Milano.

Fernando believed that Churchill wanted Mussolini dead before he had the chance to reveal that, in order to keep Italy out of the war in the desperate summer of 1940, Churchill had offered him large chunks of the former French Empire. If proved to be true, this would have greatly complicated Anglo-French relations after the war. All that my searches in Kew revealed however was that material relating to Italy in that time frame had been thoroughly purged and removed.

Fernando and I kept sporadically in touch and spoke by phone occasionally over the years. Dada and Fernando were guests at my 70th birthday party in London and we made a couple of trips together, one in my old Volvo convertible to Canterbury and Rye. We had fond memories and photos of a trip on the Bluebell line with its magnificent steam engines and comfortable old fashioned coaches. On another occasion we visited Ely Cathedral and Cambridge.

In the summer before Obama’s election as US president, Fernando and Dada invited me and my younger daughter Joelle to join them and a Milanese banker friend on a two week cruise around Sardinia on a lovely, crewed sailing yacht. Bliss. Joelle was with me in Moscow and remembers clandestinely drinking wine as the only child at the farewell party.

I won a bet with the banker, who swore that the Americans would never vote for a black president, one of many lively conversations as we sailed, swam in small bays and stopped off briefly in Ajaccio, Corsica.

During another, shorter visit to Italy, staying at their lovely home in Tradate outside Milano, we made a memorable trip not just to nearby Lake Como but to the mountains above to meet the author of a splendid book on the lake and its history and look down on one of the most beautiful landscapes in a country full of them.

Honoured to be invited to the baptism of daughter Maria’s first child in Milano in May last year, I was saddened to find that Dada and Fernando were not there as expected to witness the christening. Fernando was simply in too much pain. So it was a bitter/sweet occasion when we got back to Tradate, sad to see such a vital and lively man in pain and barely able to move, but joyful to be surrounded by Dada, daughters Giulia and Maria and their husbands and close friends. He is now at peace.

Fernando, you were close as a brother to me, as I join your family and friends in mourning your death, I am so glad that you lived and will miss you.

Obituaries in the Italian press:

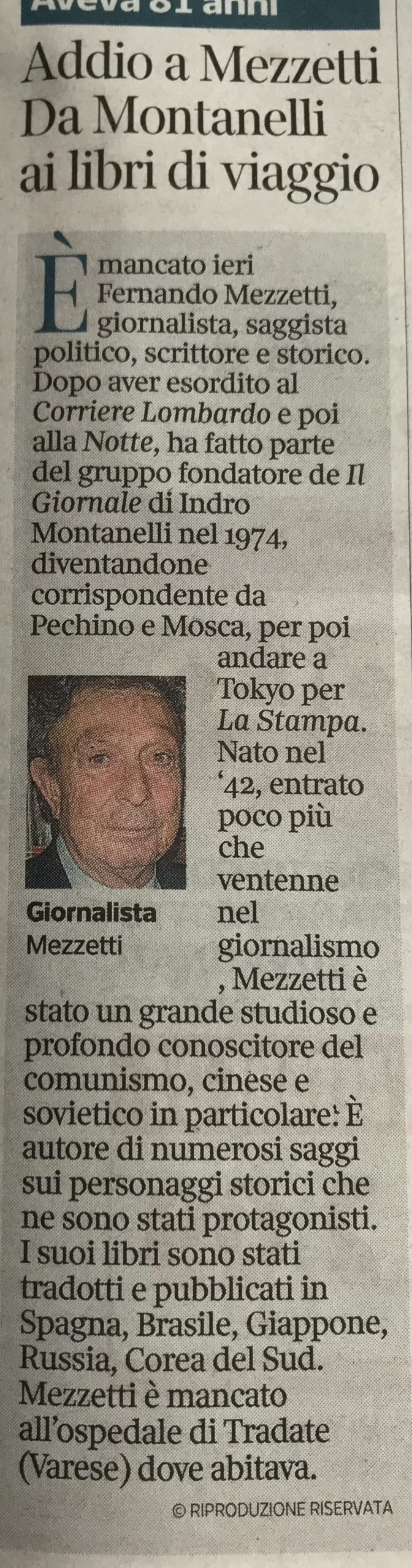

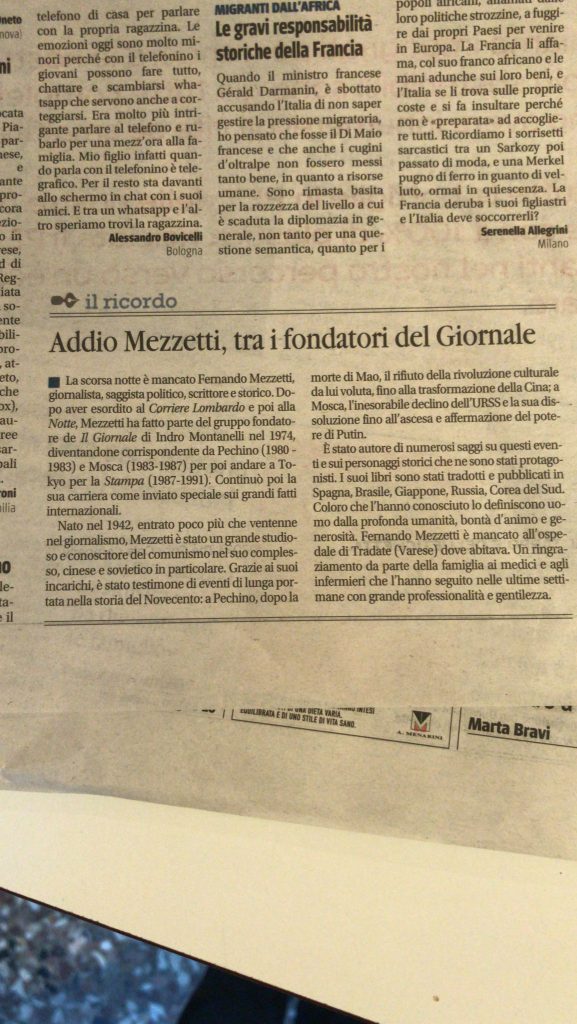

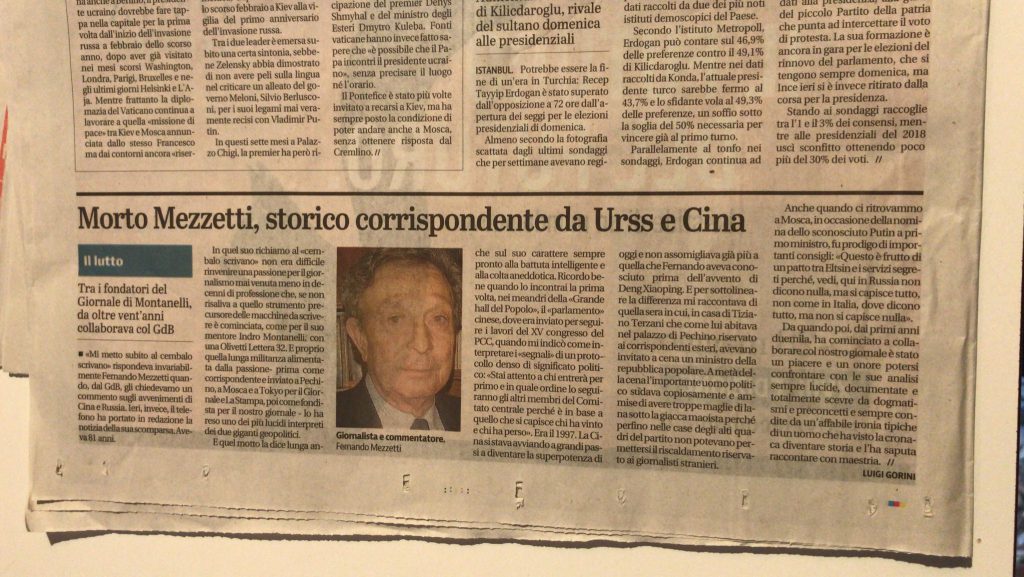

La Voce dei Giornalisti

Italia Oggi

Il Giorno

La Provincia di Varese

La Prealpina

Corriere della Sera Milan